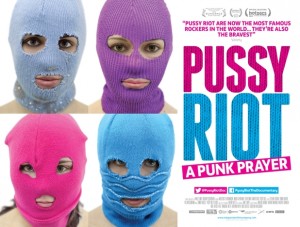

For the ECONOMIST: FOR about 30 seconds in February 2012 members of Pussy Riot, a Russian punk-art collective, staged a protest at Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Saviour. Wearing bright clothing and balaclavas they danced and shouted “Mother Mary please drive Putin away”. Security stepped in, but not before footage of their criticism of the close ties between church and state began to go global.

For the ECONOMIST: FOR about 30 seconds in February 2012 members of Pussy Riot, a Russian punk-art collective, staged a protest at Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Saviour. Wearing bright clothing and balaclavas they danced and shouted “Mother Mary please drive Putin away”. Security stepped in, but not before footage of their criticism of the close ties between church and state began to go global.

Three group members—Maria Alyokhina (Masha), Yekaterina Samutsevich (Katya) and Nadezhda Tolokonnikova (Nadya)—were arrested on charges of hooliganism inspired by religious hatred. Nadya and Masha were later convicted and are currently serving two-year sentences. Reactions have been mixed—some Western music artists have criticised the Russian court system and called for their release; many Russians are outraged by the group’s overt feminism and disregard for religion.

A compelling new documentary, “Pussy Riot: A Punk Prayer“, spends 90 minutes telling their story. Using footage from court hearings, newsreels and interviews, interspersed with the group’s rehearsals and guerrilla performances, the co-directors, Mike Lerner and Maxim Pozdorovkin, explore the impact of their punk activism. “Russia is a very conservative country, but it’s not always clear exactly what the left wing is there,” says Mr Pozdorovkin. “Pussy Riot’s feminism took conservatives by surprise.”

During the trial, hordes gathered outside the courthouse. The film shows one woman, in defense of the church, asking: “how would you feel if someone took a shit in your house?” A bearded man wearing a t-shirt that reads “Orthodoxy or Death” calls members of Pussy Riot “possessed demons”. But the director’s seem to support Pussy Riot’s message; namely that the group wants separation of church and state, Putin out, and women to be seen as more than agents of procreation. In court Nadya and Masha snicker and look bemused at times but their views are given plenty of reel-time, and they do seem to become increasingly articulate and thoughtful. Interviews with band members’ parents are enlightening. They are proud and full of love and support their children, merrily talking about their juvenile interests in conceptual art, the Spice Girls, and fighting injustice from a young age.

The film closes with Nadya behind prison bars, wishing to be free but standing by her convictions. The problem for the viewer is that the producers fail to explain the relevant laws that keep these women imprisoned. They do not examine Russia’s legal definition of “hooliganism” or whether this, and similar rulings, have perhaps aided Putin’s courts in their increased efforts to quash dissident behaviour.

The directors tell Pussy Riot’s story with sympathy but, as the film also shows, the band’s message failed to strike a chord with many in Russia. While their supporters called the verdict a degradation of human rights, others thought they deserved a harsher punishment. During a recent screening at DocFest in San Francisco the audience was less judgmental, laughing at the band’s sarcasm and mocking the man in the “Orthodoxy or Death” t-shirt. The film earned a special jury award at this year’s Sundance Film Festival.

In court, the three accused admit that the cathedral performance was perhaps short-sighted, but punk has always been about rabble-rousing. “Really, this film is about what art can strive to be,” says Mr Pozdorovkin. “[Pussy Riot] see art in a way that very few people can and do, as more than your own fame and ego.” Viewers may not agree with Pussy Riot’s actions but this film succeeds in showing how punk activism is a poignant, relevant and sometimes flawed form of expression for contemporary youth.

image: official film poster