For MOTHER JONES MAGAZINE, January/February 2019:

For MOTHER JONES MAGAZINE, January/February 2019:

In the mid-1970s, Martha Diaz was just a shy, latchkey kid growing up in New Jersey, when a friend invited her to her first breakdance battle. She was smitten. “I busted loose, became totally engaged, changed my clothes,” remembers Diaz, now 49. “It quickly became my life.” Now she makes her living as a hip-hop educator and archivist, preserving the artifacts, images, and documents of the genre and its stars. After wrapping up work on Beyonce’s multimedia Lemonade album, which required culling through some 10,000 tour photos, she’s working with Tupac Shakur’s estate to curate a traveling exhibit to launch alongside director Steve McQueen’s upcoming Tupac documentary. We asked Diaz to give us ataste for her story, and her craft.

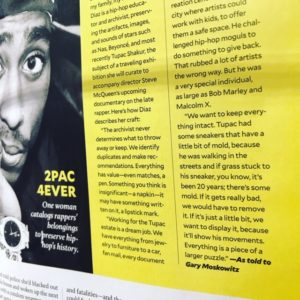

DIAZ: I specialize in moving image and recorded sound. Most of my stuff is old home movies, music videos, documentaries. The archivist never determines what to throw away or what to keep. We identify duplicates and make recommendations. Everything has value—even matches, a pen. Something you thinkis insignificant—a napkin—it may have something written on it, a lipstick mark.

I am a first generation Colombian-American. I think I was the first Latina to work on Yo! MTV Raps. I had the honor to be a production assistant, which was a gopher, you know—open up doors, find water, walk people to the stage. I got offered a permanent job as [late director] Ted Demme’s assistant. I got to meet all of the amazing, Golden Era hip-hop artists, from the Native Tongue crew to Public Enemy to Tupac. Everybody! They were all young and just starting out, but mad talented. You go to an interview at Yo! MTV Raps, it’s gonna be different than ABC. These artists were just letting loose and just being themselves. They were really pushing the envelope. Their message was strong. Their skills… whoof! They had crazy skills, whether it was Tung Twista who rapped 1,000 words in 39 seconds or someone who was so consciously capable of telling a story of the hood in poetic prose, like Nas in IllMatic. We were just breeding this special group of artists that were informing the community about struggles that weren’t being shown in the news. There was a bias during that time, showing black males ascriminals and black mothers as welfare queens. This was an alternative. This was another narrative.

MTV did not have an archiving system. They recycled tapes by taping over them, so they lost a lot of the original content. They threw away their masters. I saw a hole. I didn’t want certain pieces of the culture tobe overlooked or dismissed. That led me to help people tell their stories. When I talk about my collectors, I talk about people with 14 storage units—people who have over 50,000 records in their collection. These are people who want to be connected to the artists; they have an affinity with them and they will go out of their way and pay a lot of money to feel that connection. Wendy Williams used to say how Britney Spears had a piece of gum that she put on her plate or whatever, but somebody took that piece of gum and they sold it for $14,0001. This is why everything matters. It matters to somebody.

Working for the Tupac estate is a dream job. We have everything from jewelry to furniture to a car, fan mail, every document referring to his businesses and family history. We have about six scripts he wrote while he was in jail. We found interviews of him a few months before he passed away. Those are items that are worth more than anything in his collection, even more than the Rolex, you know? It’s not a secret that Tupac had a vision for unity in hip-hop. He wanted to correct whatever misconceptions of him causing a beef, a war, between the East Coast and West Coast.

He had this One Nation project that he was working on before he passed. He wanted to work with Snoop and other artists to create recreation centers in every city where hip-hop artists could work with the kids, to offer them a safe space. He challenged all of the hip-hop moguls to do something, to give back to the community. I think that rubbed a lot of artists the wrong way. But he was a very special individual and I agree with many of his fans that he is as large as Bob Marley and Malcolm X. We want to keep everything intact. Tupac had some sneakers that have a little bit of mold because he was walking in the streets and, if he was near grass and it was stuck to his sneaker, you know, it’s been 20 years. There’s some mold. If it gets really, really bad, we would have to remove it. If it’s just a little bit, then we want to display as is, because it’ll show his movements. Everything is a piece of a larger puzzle.

—As told to Gary Moskowitz